The characteristic mode of portraying the city in early European painting was as a cluster of towers hidden behind an enclosing barrier, and seen in the background of a scene to which it not necessarily holds a narrative connection. The urban setting is more often than not separated from the storyline of the painting. The city is a decorative addition, a distant stage set. Towards the end of the fifteenth century Venetian civic pride began to manifest itself in art. Painters like Vittorio Carpaccio or Gentile Bellini started to pay closer attention to topographical accuracy as settings for their narratives. Urban backdrops, either observed or imagined, acquired a more dominant presence and detailed presentation within the composition of their work. A contributory factor to that development in Venice and elsewhere was the ground-breaking innovations that took place in printing and the graphic arts.

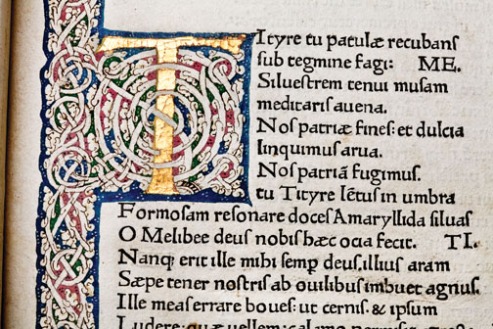

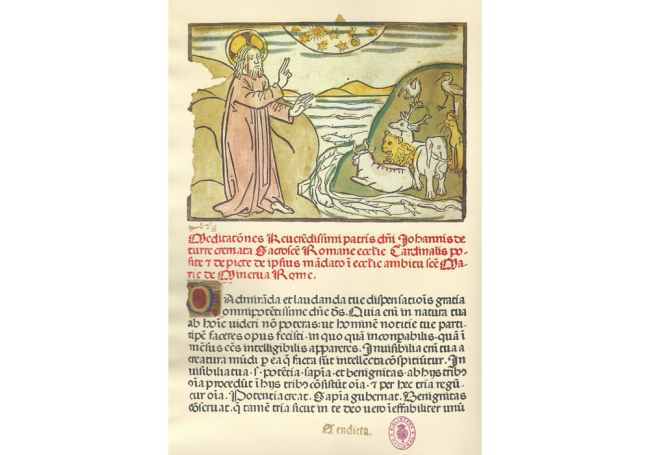

Printing had arrived in Italy in 1464, hardly a decade after the invention of the printing press, when two clerics, Conrad Sweynheym from Mainz and Arnold Pannartz from Cologne, set up shop in the Benedictine monastery St Scholastica at Subiaco, in the Sabine mountains near Rome, where they lived as lay brothers. In 1465, they issued the edition princeps of De oratore by Cicero, the first book printed in Italy. Sweynheym and Pannartz printed just three books at the monastery before moving their press to the Palazzo Massimi at Campo dei Fiori in the centre of Rome. There, they printed twenty-eight volumes in editions of up to 300 copies each. These included editions of, amongst others, Caesar, Livy, Virgil and Lucan.

However, there was no viable market for such publications and they failed to sell their stock. Sweynheym dissolved the partnership in 1473 and returned to his former profession as an engraver, while Pannartz struggled on alone until his death in 1477. The output of these and other early printers was predominantly classical texts that appealed to the small community of Humanists, but not in the least to Roman ultramontanists who were concerned with legal affairs at the papal court.

Ulrich Han another German printer in Rome produced classical texts from 1467 to 1471, by which time he was overstocked with Cicero, Livy and Plutarch. He then formed a partnership with merchant Simon Nicolai Chardella who instructed him to print books on Roman and Canon law and pamphlets pertaining to affairs at the court. This market-orientated attention meant that Han’s business began to prosper. Other best-selling publications at the time were guides to Rome’s sights and indulgences. Large numbers of German pilgrims journeyed to the city and few of them would have been able to read Latin. They were eager to purchase a travel guide, a Renaissance Baedeker in their native language. Adam Rot ran a printing press in Rome from 1471 to 1474. He was the first to publish books for visiting pilgrims, issuing several guides on the marvels of Rome. The venture proved a commercial success and the history of the guidebook was secured.

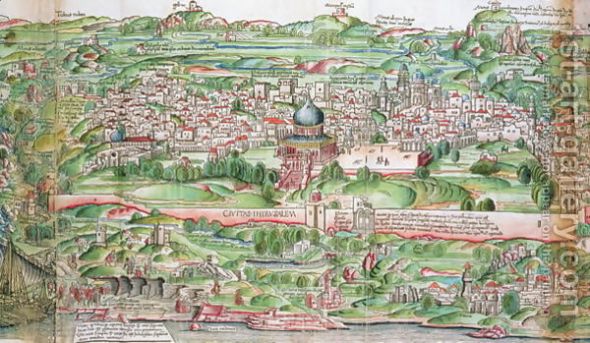

The incunable Peregrinatio in terram sanctam by Bernard von Breydenbach is one of the earliest travel books containing detailed illustrations of European and Middle Eastern cities. The book was used as a preparatory guide for pilgrimages to the Holy Land. The author’s journey took place from April 1483 to January 1484. A reckless person as a youngster and seeking salvation, he and two companions set out from Oppenheim in Germany and reached Venice two weeks later. They spent three weeks in the city which allowed the book’s illustrator Erhard Reuwich of Utrecht ample time to make sketches of his urban impressions. His image of Venice is regarded as the first purely topographical view of the city. It is significant that it appeared in a medium that that was not weighed down by traditions of narrative painting or expectations of patron or public. The book was aimed at distant readers who had never been to Venice, Jerusalem, or any of the other cities depicted and described. Reuwich created an observed vision of the city, not the background to an alternative storyline. The Peregrinatio was originally published in Mainz and became a contemporary ‘bestseller’. The splendid illustrations played a crucial part in the success of this book. Another spectacular image of Venice was published soon after. Jacopo de’ Barbari’s ‘View of Venice’ is one of the most stunning achievements of Renaissance printmaking. The aerial view was printed from large woodblocks on six sheets of paper which were then joined together to cover an area of nearly four square metres. Eleven copies are known to survive of the first state of the woodcut printed in 1500 (one of those is held at the British Museum). The original woodblocks are in the Correr Museum in Venice. The print took three years to produce and was based on careful surveys of the streets and buildings of Venice, almost every one of which can be seen clearly. It was later updated by others to reflect new building projects in a second state of the print. Publisher of the image was Anton Kolb, a merchant from Nuremberg in Germany who was resident in Venice. He recorded that no woodcut on such a size using such large blocks had ever been made before. Kolb was granted copyright on the design by the government of Venice and allowed to sell impressions for the high price of three ducats. Generally speaking, however, in artistic renderings the city remained subordinate to the representation of the religious or historical narrative. Neither painters nor patrons showed any particular interest in exploring the possibilities of producing townscapes for their own sake. The contents of the story remained fundamental to the creative effort.

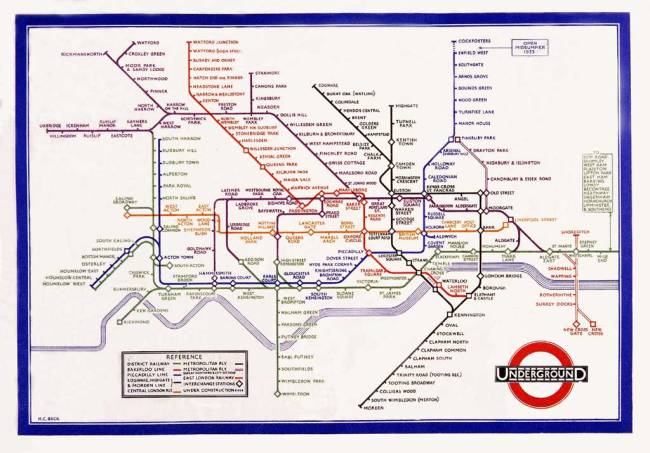

Closely associated to the emergence of travel books was the phenomenal progress made in the art of cartography. The biography of every great city is represented by the history of its maps and panoramas. In the chaos of urban growth the cartographer brings line and harmony (the map of the London Underground system is the most reassuring document the overwhelmed visitor to the metropolis can wish for). Maps and topographical drawings became a popular form of wall decoration. Monarchs, nobles and eminent citizens commissioned artists to adorn their residences with panoramas of cities, either in single sheets or in series. The sixteenth century developed a passion for geography. The expansion of travel, the Spanish and Portuguese exploration of Africa, Asia and the New World, along with the rediscovery of Claudius Ptolemy’s Geography (the earliest printed edition with engraved maps was produced in Bologna in 1477), stimulated the demand for accurate maps. Political struggle and continuous warfare contributed to this demand. An army in action needed detailed locations of possible battlegrounds and accurate views of the cities that were to be besieged. The art of map-making demanded scientific precision (no more artistic sea-monsters or mermaids in the margin) which could only be obtained through training in the use of mathematical scales and instruments.

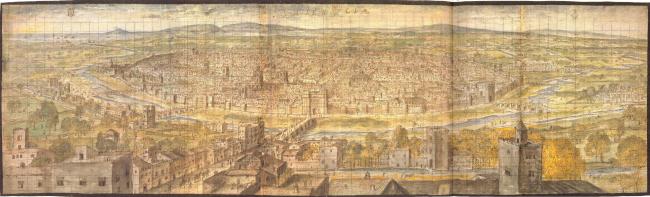

Antwerp-born Antonius van den Wyngaerde was a prolific topographical artist who produced panoramic sketches and paintings of towns in the Low Countries, England, Italy and Spain. He is recorded as saying that among all the joys that the art of painting has to offer, ‘there is not one that I hold in higher esteem than the representation of cities’. His first known work was a vista of the Dutch city of Dordrecht (historically in English named Dort) from around 1544. On a visit to Italy, he created views of Rome, Genoa, Naples and Ancona. Between 1558 and 1559 he visited England, perhaps more than once, where he made views of Dover, London and the palaces of Greenwich, Hampton Court, Oatlands and Richmond. He is best known for many panoramas of cities in Spain that he drew while employed as court artist (‘pintor de cámera’) by Philip II to whom he was known as Antonio de las Viñas. He was commissioned by the king to document all the main towns and produced at least sixty-two cityscapes (he also drew the first picture of Gibraltar). Always striving for accuracy, Van den Wyngaerde also depicted vivid town activities, but there is no trace of the squalor of street life that prevailed in all cities of that time. These images served to demonstrate the might of Philip’s Spain and give visual expression to the might of his rule.

They depended on the artist’s direct observation and visual memory – but also on his imagination. Any suggestion of realism was illusory. This is clear from his view of Valencia. The lay-out of the streets here is wide and straight as if the city had been formally planned. The squares are made larger and some of the towers moved to different positions. Despite many details, the picture is an idealized rather than an accurate representation. The same applied to his view of Granada where the size and height of churches are increased (without distorting the arrangement) in order to draw attention to the city as a ‘civitas christiana’. Shortly after the artist’s death, Philips sent the collection of views to the Plantin press in Antwerp for engraving. His likely ambition was to create a Spanish city atlas. Unfortunately, the project was never completed. Van den Wyngaerde’s views were dispersed to Vienna, Prague and London and it took until the late 1980s that the corpus of Spanish views was finally published. At the time of its creation, this record of Spanish city views was unique and without precedent. No other European ruler could boast to possess such a complete and accurate visual overview of his realms.

The first volume of the Civitates orbis terrarum was published in Cologne in 1572. This city atlas, edited by Georg Braun and largely engraved by Franz Hogenberg, eventually contained 546 prospects and map views of cities from all over the world. It provided a comprehensive image of urban life at the turn of the sixteenth century. Braun, a cleric of Cologne, was the principal editor of the work, and was supported in his project by Abraham Ortelius whose Theatrum orbis terrarum of 1570 was, as a systematic collection of maps of uniform style, the first true atlas. The Civitates was intended as a companion for the Theatrum although it was more popular in approach, no doubt because the novelty of a collection of city views represented a more risky commercial undertaking than a world atlas for which there had been a number of successful precedents. A large number of Jacob van Deventer’s plans of towns of the Netherlands were copied, as were Stumpf’s woodcuts from the Schweizer Chronik of 1548, and Sebastian Munster’s German views from the 1550 and 1572 editions of his Cosmographia. Another source was the work of Danish cartographer Heinrich van Rantzau, better known under his Latin name Rantzovius, who provided maps of Scandinavian cities. A significant contributor was Antwerp-born artist Joris Hoefnagel (with Antonius van Wyngaerde the most prolific topographical artist of his day) who not only contributed most of the original material for the Spanish and Italian towns, but also re-worked and modified those of other contributors. Plantin’s printing house in Antwerp, famous for its Polyglot Bible of 1572, was active in the fields of science and cartography as well. By offering mapmakers a space where they could interact with explorers and by supplying the know-how of printing precise and detailed maps, Christoph Plantin became a driving force behind the creation of the modern atlas. Why were the northern regions particularly active in this field of knowledge gathering? The strong topographical tradition was partly due to political developments in Germany and the Low Countries. The more Emperors Maximilian I, Charles I and Philips II tried to expand the power of imperial institutions at the expense of local city autonomy, the more these developed and sophisticated cities resisted interference in their affairs. Shared adversity created unity. It promoted civic awareness of the city’s history, its traditions, its institutions, and its cultural output. The Aristotelian concept of the’communitas perfecta’, the idea of a fully autonomous body possessing all the means of securing its own welfare and pursuing its chosen goals, supported an outburst of local pride and found expression in a variety of topographical works.

Book illustrators and map makers in particular pushed forward the development of topographical images and cityscapes. It makes the presence of Ambrogio Lorenzetti all the more remarkable. The latter was an Italian painter of the Sienese school who was active between approximately from 1317 to 1348 (the year that he died of the plague). Although few of his pieces have survived, he is considered one of the most inventive artists of the early fourteenth century. The Republic of Siena at the time was a powerful city-state where merchants and bankers had developed a strong commercial base with a range of international contacts. Politically, this was a turbulent age marred by a string of violent conflicts. Governments were overthrown and reinstated. During the late 1330s the Council of Nine (the city council) commissioned Lorenzetti to paint the ‘Allegory and Effects of Good and Bad Government’ series in the Sala dei Nove of Siena’s Palazzo Pubblico. The artist created an ensemble of urban images that is exceptional within the medieval tradition. Unlike most contemporary paintings the subject matter is not religious but civic. The aim of the painting is to exalt the political creed of the government of the ‘Nove’, a clique of Guelphs who retained power in Siena until 1355. Lorenzetti’s frescoes promoted the morality of government. By showing comprehensive cause-and-effect situations of corrupt governing in comparison to those of virtuous leadership, these images were aimed at reminding members of the council to seek justice at all times. The murals occupy three of the four walls of the Council Room. On the eastern wall Lorenzetti depicted the scenes of the ‘Effects of Good Government’, while on the western wall the ‘Effects of Bad Government’ are depicted. Overlooking both these murals, the personifications of the allegorical depictions of the virtues of good government are found on the northern wall.

In the foreground of the ‘Allegory of Good Government’ figures of contemporary Siena are represented. They act as symbolic representations of the various civic officers and magistrates. Behind them, on a stage, there are allegoric figures representing Good Government. Wisdom is seated upon a throne and holds an orb and sceptre, symbolizing temporal power. He is dressed in the colours of the ‘Balzana’, the black and white Sienese coat-of-arms. Around his head are the four letters CSCV, (Commune Saenorum Civitatis Virginis) which explains his identity as the embodiment of the Siena Council. The virtues of good government are represented by the female figures of Peace, Fortitude and Prudence on the left, and Magnanimity, Temperance and Justice on the right. On the longer wall of the room is the fresco of the ‘Effects of Good Government in the City and in the Country’. Part of that image is ‘Peaceful City’ which provides the first panoramic view of Siena. The city is filled with palaces, markets, towers, churches, streets and walls. Busy shops indicate prosperity. The fresco then blends into the ‘Peaceful Country’. The transition is made by an entourage passing through the city gate. The scene shows a bird’s-eye view of the Tuscan countryside, with villas, castles, and farmers working the fields.

The wall on which the fresco of the ‘Effects of Bad Government’ is depicted used to be an exterior wall, so has suffered damage in the past. The image shows Tyrammides (Tyranny) resting his feet upon a goat (symbolic of luxury), his hand holding a dagger, while the figures of Cruelty, Deceit, Fraud, Fury, Division, and War flank him. Above him float those of Avarice, Pride, and Vanity. The city itself is in ruin. Houses are being smashed and the streets are deserted. Crime and disease are rampant. The countryside suffers from drought and shows two battle-ready armies advancing towards each other. The disaster of bad government served as a powerful reminder to members of the council. 12 Lorenzetti supplied a painted view of a secular city in detail and inclusiveness. Commerce, trade and various social activities are visualized, while religious manifestations are almost entirely excluded. There are three identifiable churches, but they are marginal to the composition. Even the city’s impressive duomo has been squeezed into the background – no more than a tiny tower. Lorenzetti’s secular medieval city is not a faithful portrait of Siena, nor is it a true topographical representation. His ambition was to depict an ideal city, one that should be compared to Siena, but not be mistaken for it. The buildings are real structures, but the totality is imaginary. Topography is overruled by the artist’s message. His purpose was to portray the peaceful prosperity of a well-governed city. For the sake of the representation of various trades, social interaction, and communal celebrations, he re-designed the heart of the city and created a large open foreground which allowed him to display a variety of activities. That space in front of the new Palazzo Pubblico is not the Piazza del Campo, nor is it any other known open space in Siena. This large area behind the remarkably thin city-wall is a creation of the artist’s fancy. In other words, ‘Lorenzetti Square’ is an imaginary public place. The streetscape serves a particular purpose and is made subordinate to the moral message – Lorenzetti’s Siena nevertheless remains a remarkable portrait of a proud city.