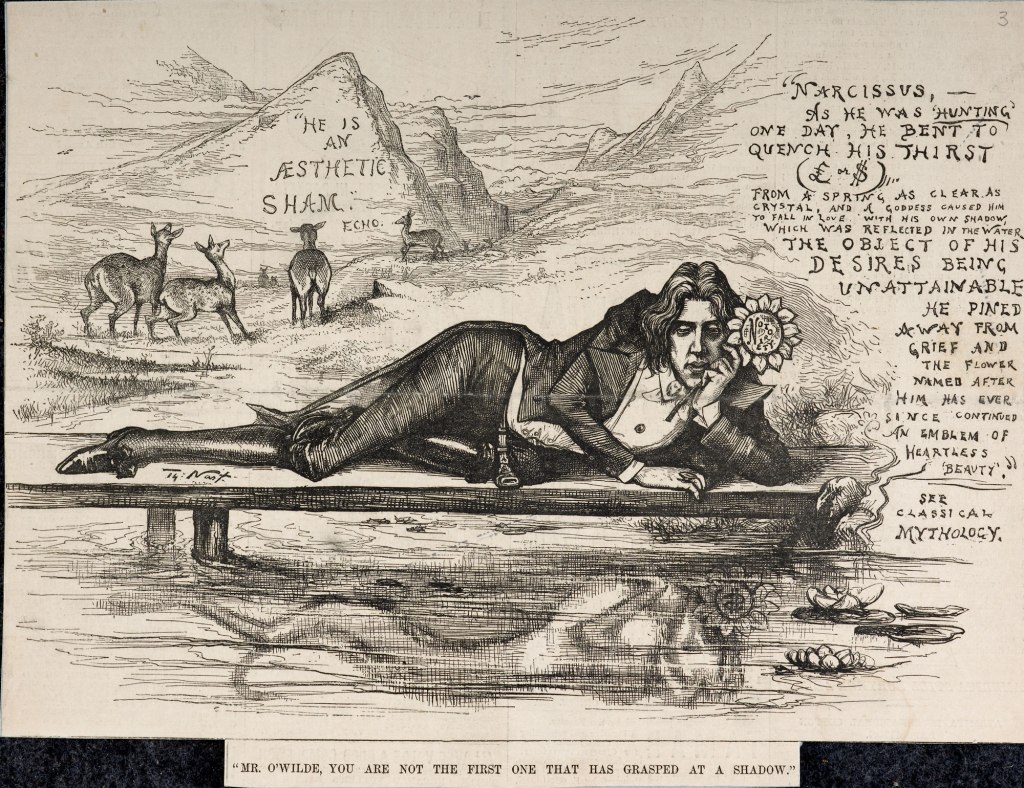

The Victorian establishment preached that art and literature fulfilled crucial ethical roles in society. If a creator dared to stray from the moral code, he was taken to court to be punished for his audacity – and so was his publisher. Critics of Émile Zola despised his ‘lavatorial’ literature and he felt the full power of repugnance when his novels were rendered into English. In 1888/9 publisher Henry Vizetelly of Catherine Street, Strand, was twice convictedof indecency for issuing two-shilling translations. The issue of ‘Corrupt Literature’ was discussed in the House of Commons in May 1888. Zola was rejected as an ‘apostle of the gutter’. To politicians and press barons, the moral health of the nation was at stake. The establishment was shocked when authors and artists of the Aesthetic Movement challenged the status quo by celebrating artistic, sexual, and socio-political experimentation. Having separated art from morality, they demanded an art for its own sake, that is: the disinterested pursuit of beauty.

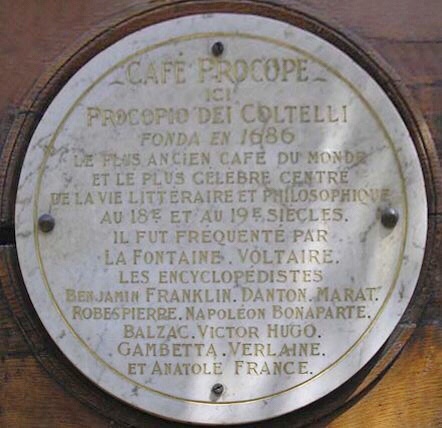

Our textbook narrative runs as follows: by the 1890s the term decadence had become fashionable and was used in connection with aestheticism. It originated from Paris and was used to describe the poetry of Baudelaire or Gautier with connotations of refinement, artificiality, ennui, and decline. Decadence was the complex literature of a society that had grown over-luxurious. From France, the movement spread to England thanks to the intervention of figures such as Walter Pater, Arthur Symons, and Oscar Wilde. For a literary movement driven forward by foreign inspiration, however, a number of conditions have to come together. First and foremost, there is a simultaneous emergence (a ‘generation’) of talented representatives; then there is the essential support of a publisher prepared to take risks; and finally, there is the need for publicity (a ‘succès á scandale’ if possible). For such a movement to find wider acceptance and lasting significance in a hostile environment, the presence of a foreign ‘ambassador’ is of particular value. All these elements came together at a property in Vigo Street, Mayfair. Running between Regent Street and the junction of Burlington Gardens and Savile Row, this street was named after the Anglo-Dutch naval victory over the French and Spanish in the 1702 Battle of Vigo Bay during the War of the Spanish Succession.

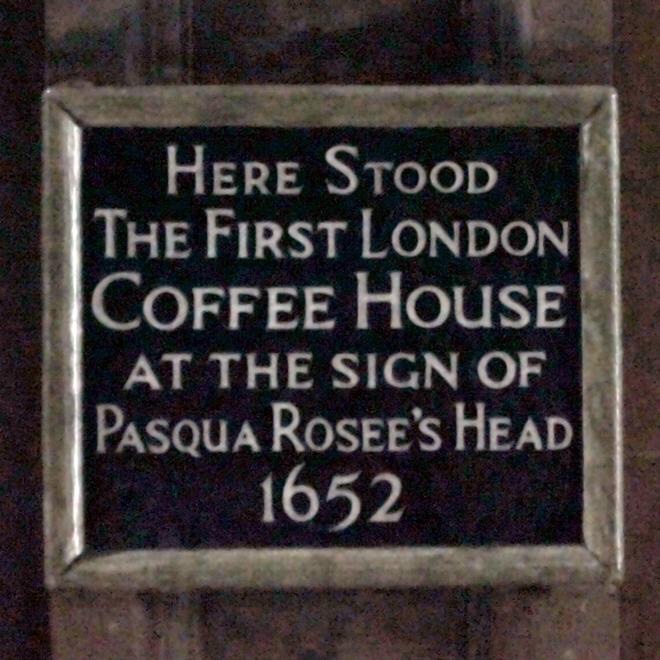

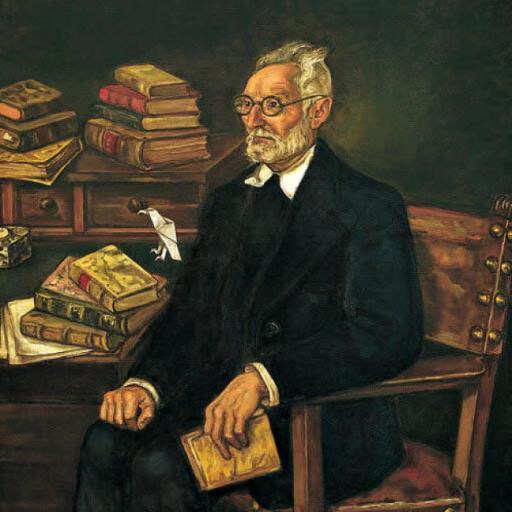

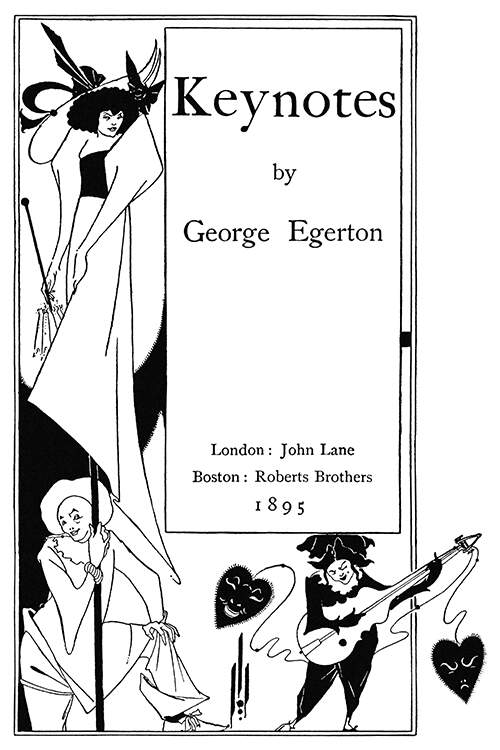

In 1887 Exeter bookseller Elkin Mathews and Devon-born John Lane formed a partnership in London to trade in antiquarian and second hand books. They established themselves at no. 6B Vigo Street, Mayfair. Over the shop door was a sign depicting Rembrandt’s head, which had been the insignia of the previous business on the site. Its new owners decided to replace the sign with that of Thomas Bodley, the Exeter-born founder of the Bodleian Library, Oxford, and call their business The Bodley Head. Initially, Lane was the silent partner, but by 1892 he became actively involved in the running of the firm. From dealing in antiquarian books the partners changed direction and began to publish contemporary ‘decadent’ poetry. The Bodley Head became a sign of modernism. Nowadays, the house is associated with Ernest Dowson and The Book of the Rhymers’ Club (1892), with Aubrey Beardsley and the cover design of Oscar Wilde’s Poems (1892), and in particular with publication of the stunning Yellow Book series (1894/7; edited by Beardsley and Henry Harland). A contributor to the periodical was George Egerton (real name: Mary Chavelia Dunne). Her Keynotes (1893) caused a sensation by tackling controversial themes including sexual freedom, alcoholism, and suicide. In the public mind, whipped up by the popular press, Vigo Street smelled of immorality. When details about Oscar Wilde’s trial became widely known in April 1895, the premises of The Bodley Head were attacked by a stone-throwing mob.

Disagreements about the running of the firm led to the partnership to be dissolved in September 1894. Lane took the sign of The Bodley Head and moved to new premises in the Albany, Piccadilly. Mathews remained in Vigo Street and published the first editions of a number of important literary works, including Yeats’s The Wind among the Reeds in 1899, and James Joyce’s Chamber Music in 1907. Lane now concentrated mainly on publishing fiction. When he died in February 1925, control of the company passed to Allen Lane, a distant cousin who had learned the book trade from his uncle. He would become the founder and creator of Penguin Books. John Lane’s ‘ambassador’ was a man whose aesthetic outlook and artistic practice were formed by avant garde movements in Antwerp, Brussels, and Paris. The Bodley Head helped push the career of a Belgian poet and illustrator and, in doing so, integrate Continental modernism into mainstream British art and literature.

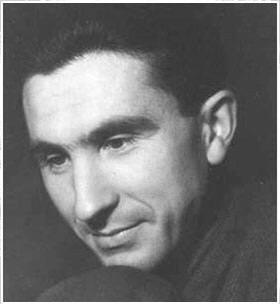

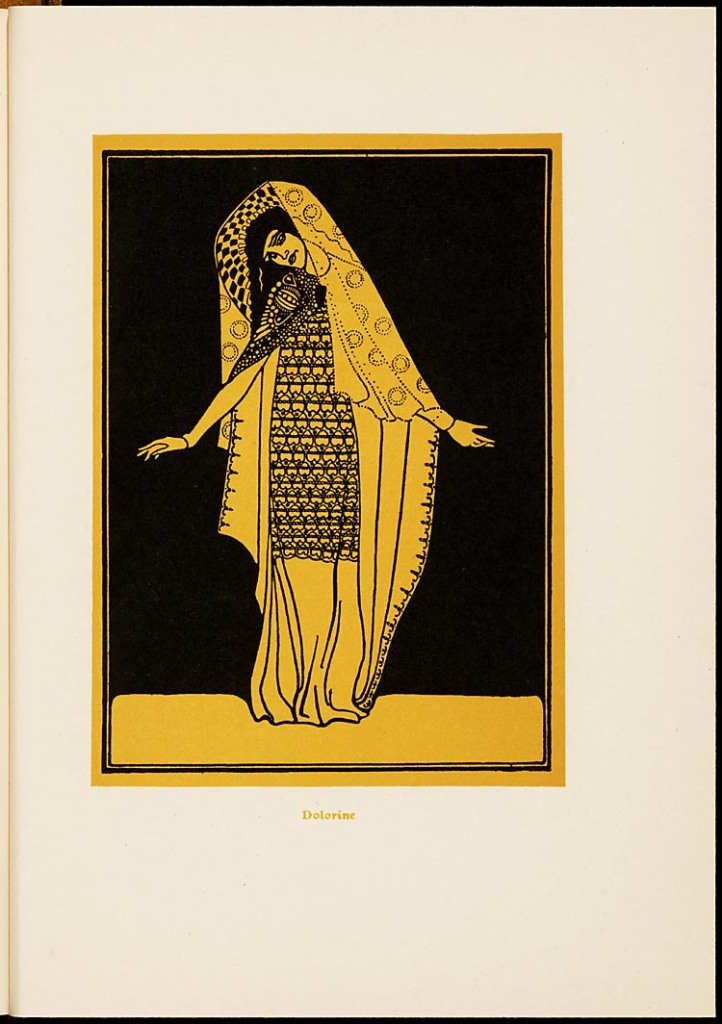

Jean de Bosschère was born on 5 July 1878 in Ukkel (Uccle) in the Brussels region. He spent his childhood in Lier and studied art in Antwerp during the late 1890s when the city’s cultural scene was dominated by Art Nouveau. He began writing essays and monographs on (Flemish) art. He published his first collection of poetry Béâle-Gryne in 1909 to which he added his own illustrations in the style of Aubrey Beardsley. He also drew inspiration from Paul Claudel’s spiritual (Catholic) writing and the (French) symbolist poetry of his friend Max Elskamp. The theme of his first ‘poem-novel’ Dolorine et les ombres (1911) is the opposition between life and dream, between divine and profane love. Its content provoked an accusation of Satanism. The book was printed by Paul Buschmann (the ‘house printer’ of the Antwerp Society of Bibliophiles) in a limited edition of 250 copies. His approach was inspired by William Morris’s Kelmscott Press in its ambition to create a perfect harmony between page, typography, and illustration. The Antwerp-based artist René Leclercq provided the novel with a portrait of the author. The impeccable presentation of this novel, aimed at a limited audience, set a precedent for all his later publications.

When World War I broke out, De Bosschère fled to London and settled in Hampstead. John Lane recognised his talent as a poet-illustrator and appreciated the hothouse temperature and erotic sophistication of his creative endeavour. In 1917 The Bodley Head published a collection of his poems under the title of The Closed Door. The translator of these poems was a significant figure. Frank Stuart [F.S.] Flint was a prominent member of the Imagist group. A poet and translator with a sound knowledge of French modernist literature, he ‘competed’ with Ezra Pound for being the brains behind the Imagist movement. The collection made an impact and the poet was admitted to the London elite of modernists. He influenced T.S. Eliot and befriended Pound, Joyce, Huxley, and others. In 1922, tribute was paid to his work by the American translator and Romanist Samuel Putnam in The World of Jean de Bosschère, published in an edition of 100 luxurious copies (with a letter of introduction by Paul Valéry). It cemented his place in the English-speaking world.

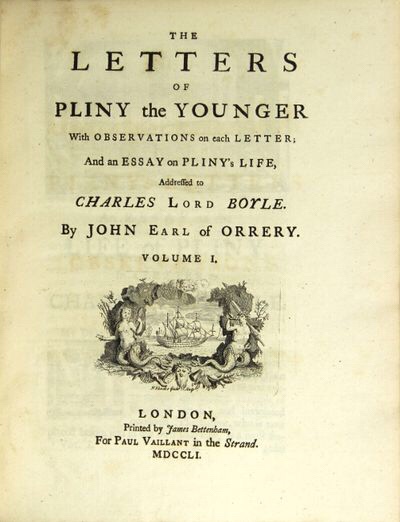

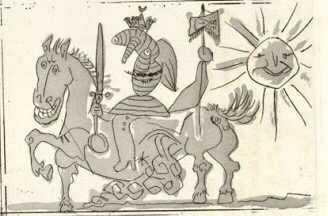

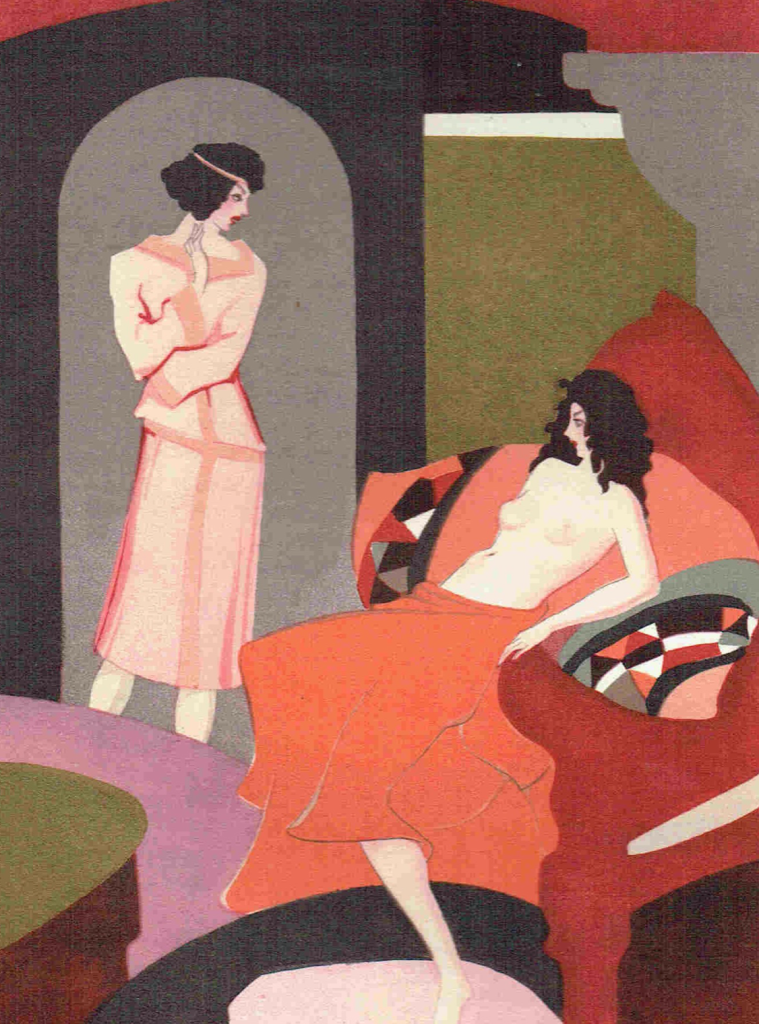

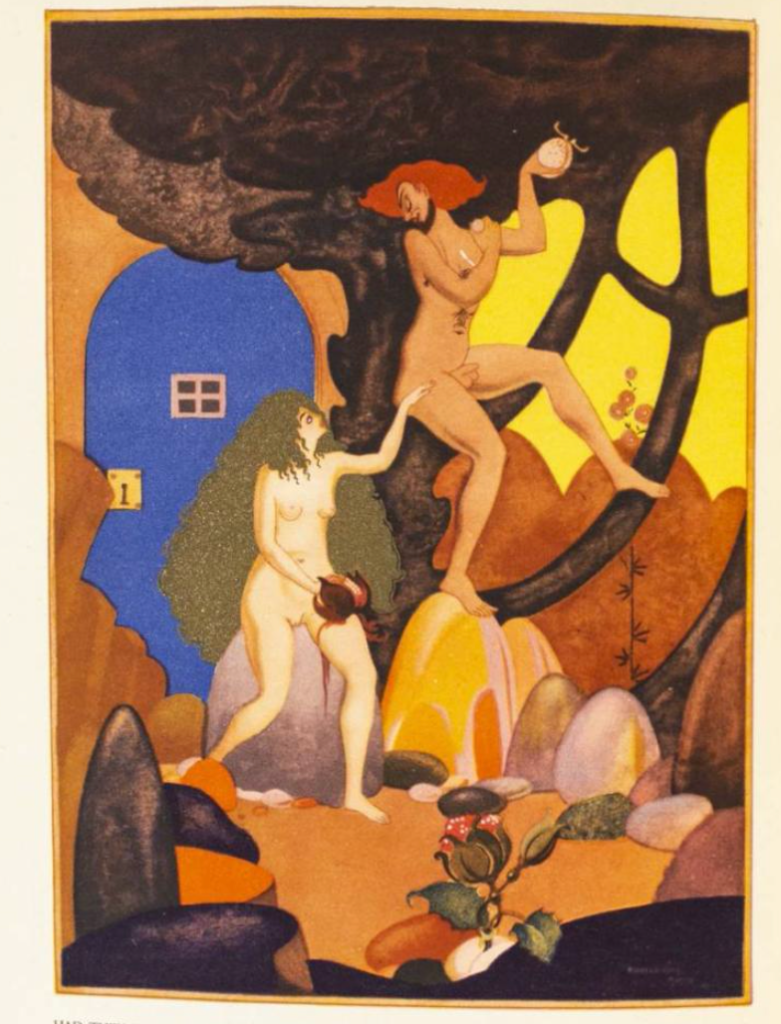

A period of intense activity would follow. He illustrated classic works by Aristophanes, Ovid, Strato, and Apuleius, but he was very much involved with contemporary literature too. In 1927, he illustrated the Boni & Liveright edition (New York) of The Poems of Oscar Wilde. In 1928 he produced the plates for Baudelaire’s Little Poems in Prose, translated by Aleister Crowley, and published in a limited edition of 800 copies. Two years later, he enriched Richard Aldington’s translation (from the French) of Boccaccio’s Decameron with fifteen full-page colour plates. His distinctive, often grotesque style of fantasy illustration (with reminders of Jeroen Bosch) fitted children’s books as well. He authored and illustrated The City Curious (published by Heinemann in 1920), a masterpiece that rivals the achievements of Lewis Carroll. The choice of material indicates that his work was marked by a fascination with the erotic, the obscure, the child-like, and the occult. The pioneering technique of chromolithography as a method of colour printing which was developed in Paris by Godefroy Engelmann and refined by his son Godefroy II during the latter decades of the nineteenth century, did lend itself very well for his work and he applied the technique with great skill. It made him was one of the great colour-plate artists of the early twentieth century.

Apart from The Closed Door, John Lane published four more of books in which Jean de Bosschère participated:

1922: 550 copies of De Bosschère’s Job le Pauvre with fourteen illustrations by the author; frontispiece by Wyndham Lewis; text in French & English.

1923: 3,000 copies of The Golden Asse of Lucius Apuleius; translated by William Adlington; introduction by Edward Bolland Osborn; illustrated by De Bosschère.

1924: 3,000 copies of Gustave Flaubert’s The First Temptation of Saint Anthony; translated by René Francis from the 1849/56 manuscripts; illustrated by De Bosschère.

1925: 3,000 copies ofThe Love Books of Ovid; a translation of Ars Amatoria by J. Lewis May; illustrated by De Bosschère.

The author and illustrator himself was back in continental Europe by then. His love affair with the translator Vera Anne Hamilton had blossomed in 1920, but she died two years later. He left London towards the end of 1922, spending the remaining years of his life in Paris, Brussels, and Sienna, where he worked on his novels and poetry collections. He remained a prolific artist, but his days of glory were gone. With the darkening socio-political atmosphere of the 1930s, modernist artists came under attack. The general movement was away from individual vision towards joined values. Contemporary society was attacked for the disintegration of principles and decline of moral authority. The brutality of Nazism, the fury of Fascism, and the emergence of Bolshevik realism, dealt a mortal blow to modernist exploration. De Bosschère’s work sunk into relative obscurity. He died in January 1953 in France. From 1946 onwards, he kept a diary titled Journal d’un rebelle solitaire (as yet unpublished). Jean de Bosschère’s work deserves a catalogue raisonné – urgently.