Boost, Baste and Lambast (How to Poach a Periodical)

On 27 January 1990 a ninety-three year old man named Alfred John Barret died in the cathedral city of Wells in Somerset. He was cremated and his ashes scattered. Having moved from London in 1952/3, he had lived in Wells for some four decades with his Scottish wife, leading an unassuming life in a modest red brick housing estate. His death went unnoticed.

Alfred Perlès was born in 1897 in Vienna. His father was an affluent Czech Jew; his mother French and Catholic; his education Austro-German in the tradition of Goethe, Hölderin, and Mozart. As a young man he had the ambition of becoming a writer and, according to his own memoirs, he had sold a German-language film synopsis shortly before the outbreak of war – his only pre-war publication. Apparently there were several novels (or fragments thereof) written in German, but these were never published. During World War I he served as a junior officer in the Austrian army. Having been sent into action in Romania, he was court-martialled for a serious dereliction of duty and spent the remaining years of the war in an asylum. After the war he left Vienna never to return. The first phase of his life had ended in disgrace.

Carrying a Czech passport and very little money, he roamed through the streets of Berlin, Copenhagen and Amsterdam, before arriving in Paris around 1920. When his affluent parents realised that their son had falsely told them that he was studying medicine at the Sorbonne, they stopped sending him money. Battling extreme poverty, he held a variety of odd jobs and survived in the margin of society, acquiring a ‘wolf nature’ (his own term) with a street instinct for securing shelter and food. He lived the life of the wandering artist: exiled, rootless, and assuming numerous identities (his aliases were Alf and Joey and Joe and Fredl; he was the infamous Carl of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and Quiet Days in Clichy). Perlès was one of the ‘Internationale’ of drifters in Paris – possessing an amazing ability to adapt to new socio-cultural surroundings. He quickly began writing in French and thought of himself as standing in the tradition of Joseph Conrad, Ionesco, Samuel Beckett, or William Saroyan. They all had adopted a foreign tongue and made creative use of it. To Perlès it was a condition of modernism: writing in another language intensifies one’s consciousness, opens new horizons, and deepens the range of feelings and sensations.

Perlès met Henry Miller when the latter first visited Paris in April 1928, but it was not until early 1930 that their close friendship began. At the time, Perlès was scraping together a living as a journalist, writing feature stories for the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune. Miller once described Perlès’s existence in the metropolis as the ‘life of a cockroach’. Miller himself was in an even worse state, broke, starving, and homeless. Perlès offered him all the help he could afford. They became roommates in Clichy, a poor district just outside Paris. Six years older than his companion, Perlès was Miller’s mentor in how to survive hardship and be an artist. Miller memorised the experience in Quiet Days in Clichy (written in 1940; published in 1956). Together they penned a pseudo-manifesto called ‘The New Instinctivism: A Duet in Creative Violence’ (1930). In 1936 Perlès wrote his first French novel Sentiments limitrophes. Creatively, these intimate friends and artistic rivals spurred each other on.

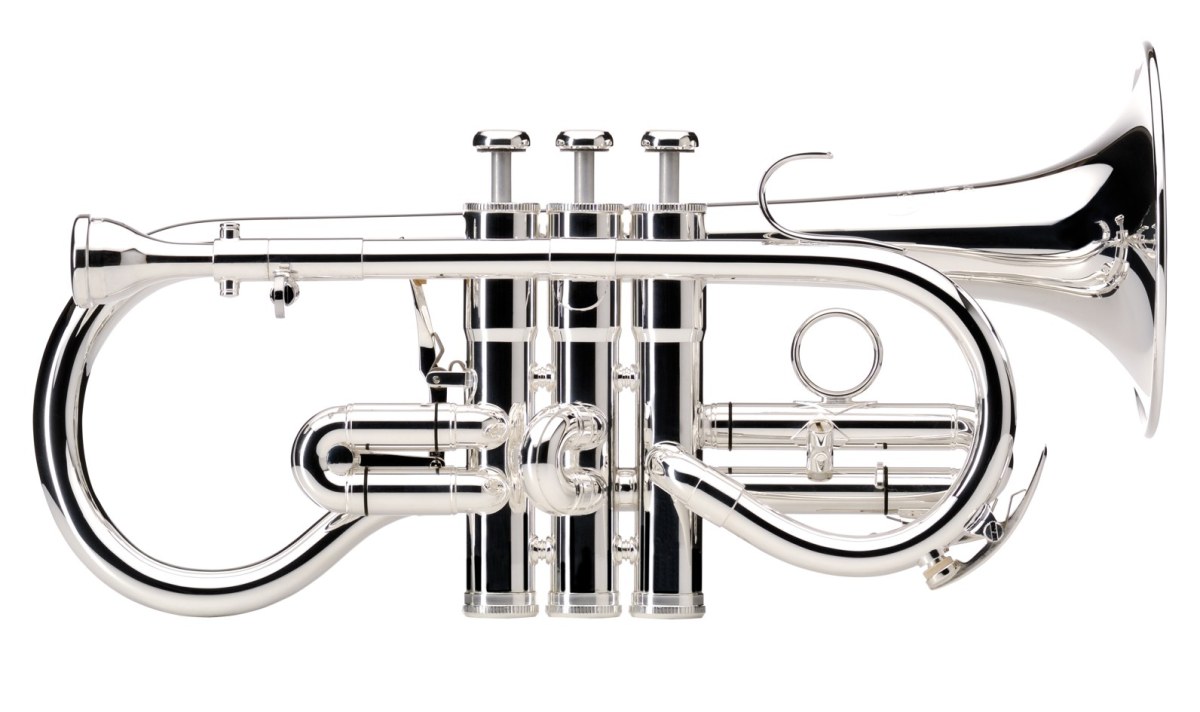

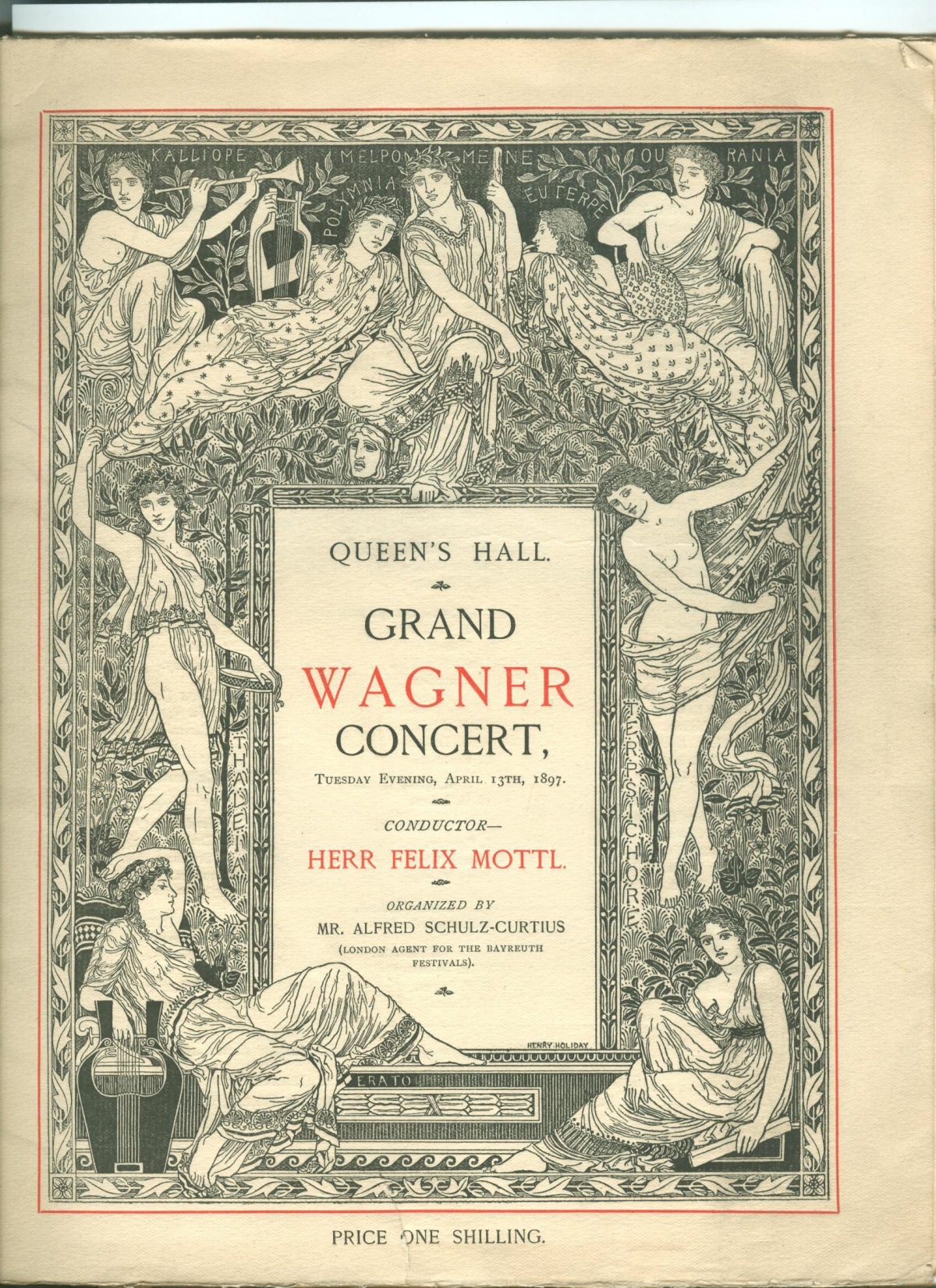

In 1934 Perlès was made unemployed once again with the closure of the Chicago Tribune office. Soon after, an unexpected opportunity came his way. Situated about twenty miles east of Paris, the American Country Club of France had been founded by elderly businessman Elmer Prather for the pleasure of affluent Anglo-American expats and a handful of local lovers of the game. The Club also provided its members with tennis facilities and a swimming pool. Prather launched a monthly magazine with club notices, sporting news, and advertisements for golf clubs, waterproof clothing, etc. Lacking editorial expertise, he decided to delegate the job to a professional. In 1937, he handed over ownership to Perlès on condition that the magazine’s old name be kept and its connection to the Country Club maintained by printing in each number two pages of golf news. For Prahter it seemed a shrewd move. The editorial responsibility was given to a proper writer whom he did not have to pay. At the same time he would have his notices published for free and the Club’s name would benefit from its association with a quality magazine.

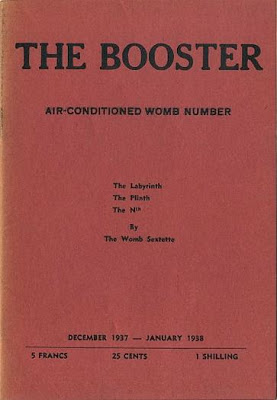

It was a golden opportunity for Perlès & Friends. Together with Henry Miller, Lawrence Durrell, and Anaïs Nin, he poached the journal and turned it into an avant-garde enterprise (in English & French). Modernism was the motivator. In a letter soliciting subscriptions, Henry Miller announced that the editors were planning to ‘boost, baste and lambast when and wherever possible. Mostly we shall boost. We like to boost, and of course to begin with we are going to boost ourselves’. In the wider Parisian artistic scene, the modernist idea had been pushed forward in countless manifestos that were diffused in a flow of little magazines. Manifestos were battle cries, not sets of rules and regulations. One of the ambitions of the movement was to abolish all directives that had been imposed upon writers and artists. Modernist art was spontaneous rather than ‘programmed’. The Booster took a unique place in that tradition. Its starting team was impressive: managing editor: Alfred Perlès; society editor: Anaïs Nin; sports editor: Charles Nordon (Lawrence Durrell); butter news editor: Walter Lowenfels; department of metaphysics and metapsychosis: Michael Fraenkel; fashion editor: Earl of Selvage (Henry Miller); literary editors: Lawrence Durrell and William Saroyan.

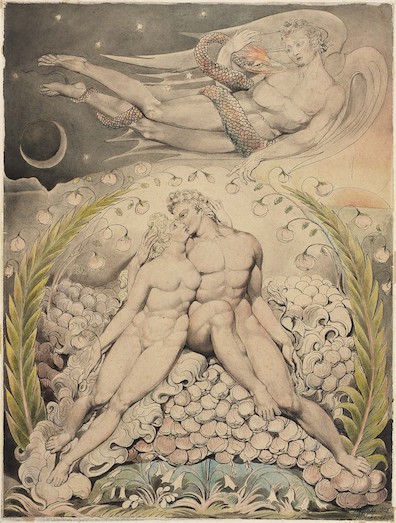

Since the magazine was dependent on advertising patronage of the golfing elite, a measured approach would have been a pragmatic position to take. The opposite was the case. The editorial stance was uncompromising and subversive. Financial backing soon dried up and was halted with the publication of Nukarpiartekak, a Greenland saga which had been brought to European attention in 1884 by the Danish explorer Gustav Holm.* It tells the tale of an old bachelor, a lustful Eskimo, who disappears entirely in the vagina of a young woman. What is left of him is a small skeleton she passes into the snow the next morning. The publication was publicly denounced as obscene by the Club’s president. The magazine changed its name to Delta. It ran for another three issues before being discontinued. Boosting was no longer acceptable.

In 1938 Alfred published his second French novel Le quatour en ré majeur. Soon after, the band of friends broke up. Miller moved to Greece and Perlès fled to London. The Bohemian stage of his life came to an end. After coming to England in December 1938, he was briefly interned (he recorded his experiences in 1944 in Alien Corn). On his release he joined the British Pioneer Corps helping to clean up rubble after the Blitz. He turned into a British patriot, concerned about the future of humanity and with an intense hatred of Nazi Germany. He expressed a moralistic seriousness which his friends of old greeted with dismay. He suggested in writing that he ‘had conquered the futility’ of his existence and emerged on ‘a higher plane of life’. He may have regretted his wild years in Paris, but there remains at least a linguistic link between his involvement in the avant-garde and his activities in the Pioneer Corps. By the mid-fourteenth century the word ‘pioneer’ (of French origin) referred to foot soldiers who marched ahead of their regiment to prepare the way, dig trenches, clear roads and terrain, with their picks and shovels. Pioneers were send in advance of the army. Napoleon’s use of the term avant-garde was identical before it became a cultural metaphor.

In 1943 Perlès published his first novel in English, entitled The Renegade. Around this time, he met Anne Barret who became his partner and later, in 1950, his wife. At the time of his naturalisation on 11 November 1947, he was living at Lissenden Mansions, Highgate Road in Kentish Town. By then he had changed his name to Alfred John Barret. In 1952 the couple moved to Wells. Perlès and Miller maintained a lifelong friendship. Miller visited Perlès in Britain and Perlès went out to see Miller in 1954/5 in Big Sur, California, where he wrote My Friend Henry Miller. In 1979, Miller composed a tribute to Perlès in the memoir Joey (the name given to him by Miller and Nin). The latter’s autobiography Scenes of a Floating Life is out of print (and should be re-issued). His relative quietness as an author in Britain and his disappearance from public life is intriguing and goes deeper than a more ‘mature’ outlook at life.

Ironically, it was the friendship with Miller that lies at the bottom of Alfred’s reduced creative powers. Perlès was a floater, an individual who was able to assume a variety of identities and act out different parts without ever belonging to any specific cultural group. He drifted from Vienna, to Paris, to London, writing in German, French, and English, but was unable to find a sense of totality or personal completeness. His psychological make up was as bewildering to himself as it was to others. He never showed the force of character to channel his creative talent. Young Miller was of a different disposition. Working in Paris on his first novel Tropic of Cancer, he submitted himself to a set of rules which were formulated in the process. It was a program of obsessive work based on a regime of relentless self-discipline. Sustained creation is not possible, but work always necessary (Miller was the fastest typist Perlès had ever met in his life). In the end, Miller’s sheer creative power inhibited his friend. It proved impossible to wrench himself free from the presence of genius. Perlès was acutely aware that his younger roommate would overshadow him in creative achievement – in the domain of ultimate human pride. He withdrew into the quiet splendour of England’s smallest city.

* Nukarpiartekak – Modernist Magazines Project – Magazine Viewer

http://www.modernistmagazines.com/magazine_viewer.php?gallery…article_id=681